Jenny Montigny’s Wikipedia page gives already a good insight into who she was. In brief: a talented daughter born into a typical upper middle class Bourgeoisie family in Ghent, she wanted to become a painter against the wishes of her parents and the applicable standard of the late 19th century bourgeoisie. She took lessons with Emile Claus, the master of Flemish Impressionism. She became his ‘dearest student’ and booked international success under his wings.

When Claus died in 1924, Impressionism was on its return and interest in Montigny’s work also dropped. She died in poverty in 1937, her work largely forgotten.

Even though Claus’ work was praised and honoured in the years afterwards and named as the ‘greatest impressionist of the low countries’, Montigny had always remained in his shadow even though many art connoisseurs (including our own art historian Mieke Ackx) believe that her work should stand alone and deserves its own spotlight.

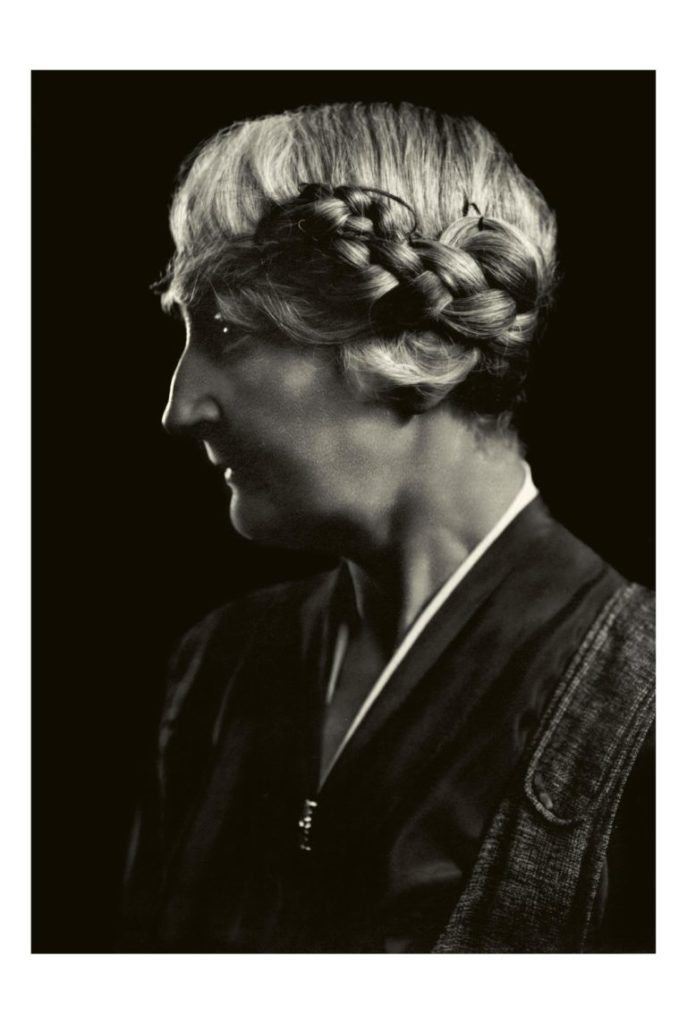

Moreover, her whole life was dominated by extreme perseverance, something you would not have associated with the rather timid appearance of this young woman.

The birth of an artistic talent

Joanna (Jenny) Montigny was born on the tenth of December 1875, the child of the upper class French-speaking, Ghent bourgeoisie. The family lived at Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat 118.

Father Louis Charles Auguste Montigny combined a job in the East Flemish provincial administration and was a lawyer, as well as a professor at the law faculty of Ghent University. In addition, he was a member of the city council and was an elderman for a while. Father Montigny was known as a pragmatic man, who did not support the fine arts. One of his statements he made can illustrate this : “J’offusquerai, peut-être, les amateurs d’art mais je dois dire que les considérations émises point de vue artistique me laissent absolument froid” (translated: I may offend the art lovers, but I have to say that artistic concerns leave me absolutely cold.’) (photo credit: Ugent)

Jenny’s mother, Joanna Helena Mair, was born in Ghent but came from a Dutch-Scottish merchants’ familiy who arrived in the Southern Netherlands in the 1930s. Most likely, the family was active in textile trade and/or manufacturing. (Photo credit : private archive)

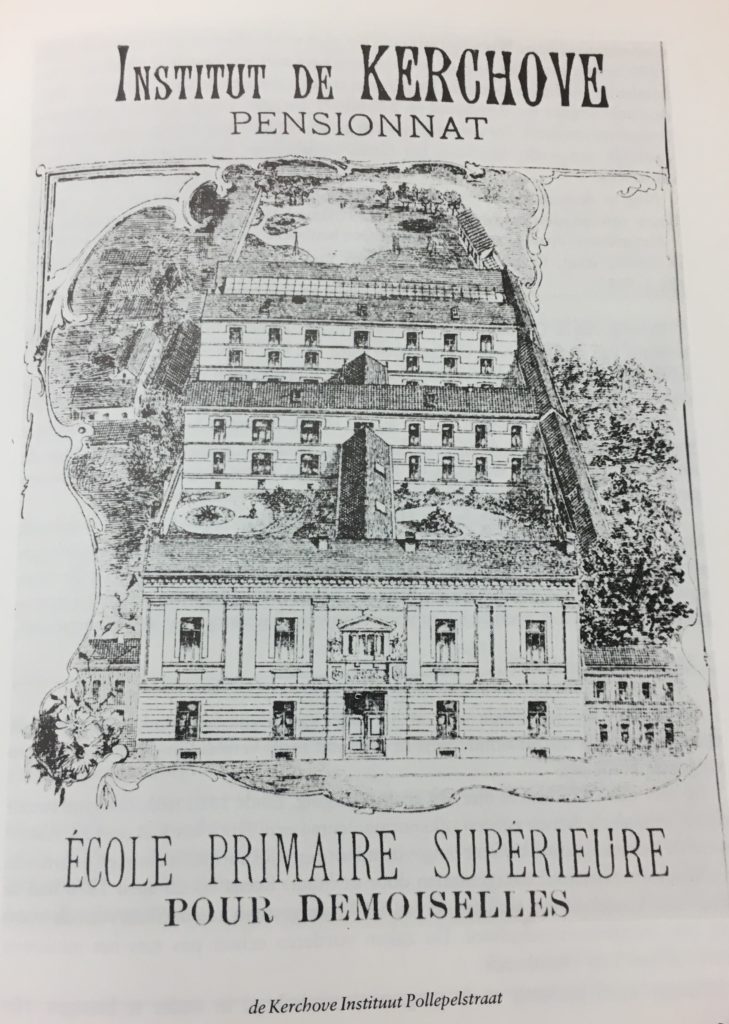

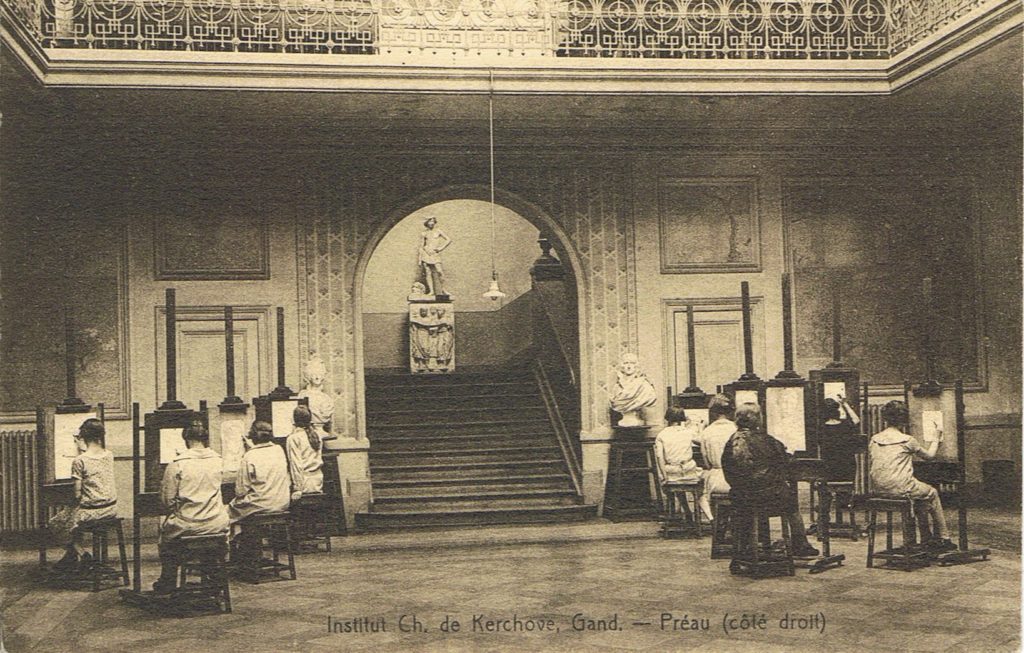

Jenny Montigny and her two sisters, Louise and Yvonne, received a typical education : they went to a prestigious ‘girls’ school Charles de Kerchove. This French-speaking private school – outspoken liberal and anti-clerical, located in the Pollepelstraat, provided secondary education for young girls coming from a ‘good home’. The curriculum focused on language skills (French, Dutch), reading, writing, maths, history, geography and handicrafts. It was not really an artistic education, but ‘tout ce qui comporte l’éducation des jeunes personnes destinées a vivre dans la société et jouir d’un état d’aisance’. (translated : ‘everything that includes the education of young people who are destined to live and enjoy a welfare state.’) (photo credit : School van Toen – Ghent)

Young Jenny soon showed her artistic talent. According to some sources, she even received extra drawing lessons. This was certainly not uncommon for well-educated young ladies from the upper bourgeoisie. Painting and drawing was considered a mere ‘passe temps’, a pastime. Such skills were seen as an extra quality in the search for a suitable spouse. However as a young lady to paint professionally was totally ‘not done’ and almost reprehensible. (photo credit : liberas, liberal archive)

It has been said that during a visit to the Museum of Fine Arts of Ghent in 1892, 17-year-old Montigny was full of admiration for the canvas ‘The Kingfishers’ by E. Claus. The work, painted in 1891, made such a big impression on her that it continued to haunt her. And a little later, she looked for the artist who created the ‘Kingfishers’.

For that time, this disobedient, almost rebellious attitude of a young lady from a civil and very protected environment was very remarkable. According to some sources Jenny broke with her family and their education to become an artist. But that is unlikely. They will not have approved of it, but multiple clues suggest that they complied with her choices and even provided for it. Jenny Montigny knew however, in her immediate family circle, a female artist. On 13th September 1890, Jenny is just under the age of 15, when her cousin Albert Louis Mair, marries the painter Gabrielle van Meerbeke. Gabrielle Mair-Van Meerbeke is a completely forgotten painter. Yet, she may have been of great importance in Jenny Montigny’s artistic development.

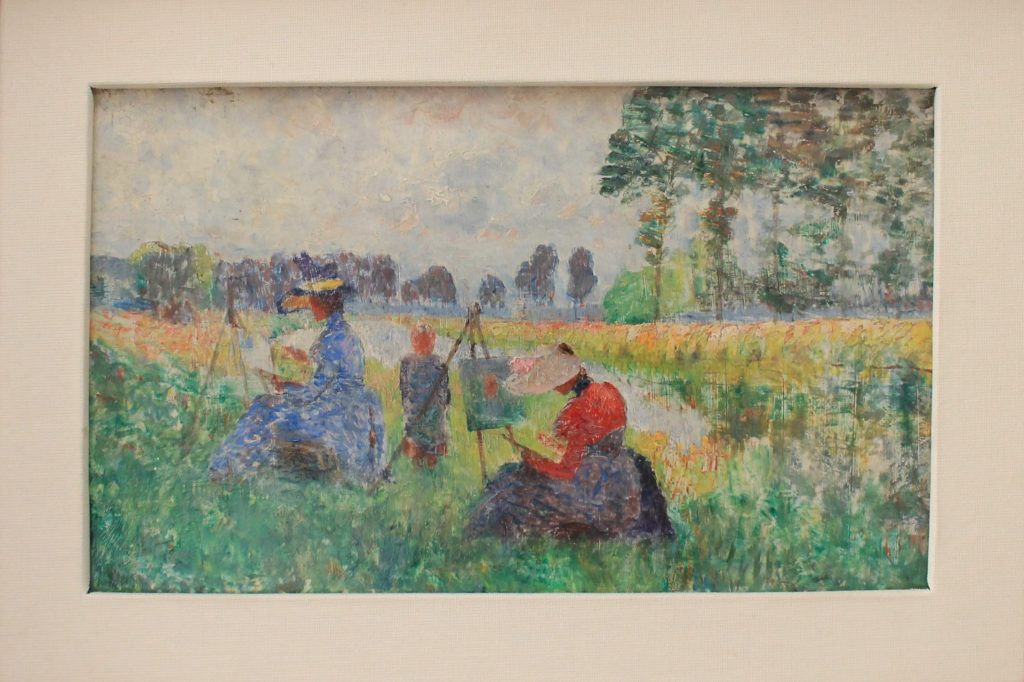

Whatever is true, in the summer of 1895, Jenny took up painting lessons in the open-air classes of Emile Claus, at Villa Zonneschijn in Astene near Deinze. She ended up in Claus’s circle of pupils and friends, including Anna De Weert, Anna Boch, Georges Buysse (brother of Cyriel), Yvonne Serruys, Marie-Antoinette Marcotte, Rodolphe de Saegher, Georges Morren, Baroness della Faille d’Huysse, The American Robert Hatton Monks and the Japanese Torajirō Kojima. In addition to students and colleague- artists, also writers surrounded Claus. He is known to have maintained a close friendship with Cyriel Buysse and Camille Lemonnier. This cheerful, young company was known even well known as far as Paris as ‘la Clauserie d’Astene’. (photo credit : private archive)

La Vie d’Artiste

Between 1895 and 1904 Jenny Montigny commuted regularly between the family home in Ghent and Emile Claus’ Villa Zonneschijn in Astene.

In 1902 she made her professional debut at the Triennale of Ghent with five of her works. Emile Claus was also on the selection board. It was mainly the monumental work ‘September morning’ that made an impression. It referred ‘sans gêne’ to Claus’s 1890 masterpiece, ‘The Beet Harvest’. In that same year Emile Claus painted an exceptional beautiful portrait of the young Jenny Montigny, sitting in a garden, with a dreamy, somewhat absent look.

Jenny exhibited in Paris in 1903. In the following years she was also regularly present at the Paris Salons. Therefore it seems very likely that during those occasions she could have been introduced to the works of female painters such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassat.

In 1904 Jenny Montigny settled in Deurle, a stone’s throw away from Astene. She built a villa just outside the village centre, near the station, called ‘Rustoord’. Officially, she lived there with her younger brother Louis. (photo credit : private archive)

Her move to Deurle will not only have been for her desire to have artistic freedom. It is in those years that a ‘more romantic relationship’ formed between the master and his beautiful, talented pupil. There are few to no factual traces to assessess their romance. However, there are multiple clues that go beyond the same circle of acquaintances, the shared artistic interests and the fact that they often exhibited in the same places.

The lifelong bond between Montigny and her 26-year-older married mentor Emile Claus is also inevitably a source of much rumour and gossip in the villages of Astene and Deurle. Emile Claus was called by his contemporaries and later biographers as a great ’causeur’ and ‘charmer’, ‘who was also… approached by several ladies and… envied.”” On trips or travels, Montigny and Claus exchanged letters and postcards, mostly written in English, probably to make it a little bit more difficult for housekeepers to read them unsolicited. (photo credit : private archive)

Jenny’s radical choice for an independent artist’s existence and a non-conventional love life does not cause a break between her and her bourgeois family. The faimily probably will not have been enthusiastic, but apparently it was tolerated.

The fact that Nancy Mair, Jenny’s mother, died on 31st May, 1904 in Villa Rustoord, certainly is an indication that there was a close, intense bond between the quirky daughter and the family. When Jenny’s niece, Nancy Willems, got engaged to Fernand Vanlangenhove in 1922, photographs were taken of the couple in Aunt Jenny’s studio. In that picture, Emile Claus joined the family in a clearly casual atmosphere which again points to a form of family acceptance of this eccentric relationship. (photo credit : private archive)

In 1904 Montigny also joined the artists’ association ‘Vie et Lumière’. Among its founding members, this art circle included names such as Anna Boch, Anna De Weert, Georges Buysse, Emile Claus, William de Gouves de Nunques, Aloïs Delaet, Rodolphe De Saegher, James Ensor, Alfred Hazledine, Adriaan Jozef Heymans, Georges Lemmen and Georges Morren.

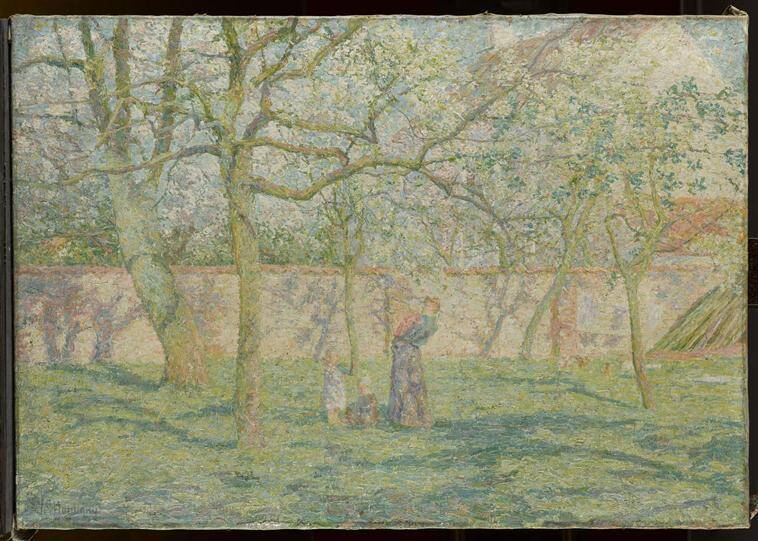

1906 was a miracle year for Montigny: she received invitations to participate in three Parisian salons, the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-arts, the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne. The French government purchased her canvas ‘Still Life with Roses’ at the ‘Salon des Indépendants’. Henry de Rothschild donated ‘Flowering Orchard’ to the Museum of Lille, which she exhibited at the ‘Salon d’Automne’. She was also very visible in her own country that same year: she exhibits 8 canvases in the Cercle d’Art Vie et Lumière in Brussels and at the Salon Triennal de Gand. In 1913, the Museum of Fine Arts of Ghent bought ‘De Tuinier’.

The young artist received good reviews, on the other hand the reviewers almost unanimously continued to emphasize the very strong influence of Emile Claus. (photo credit : musée des Beaux-Arts Lille)

The Great War

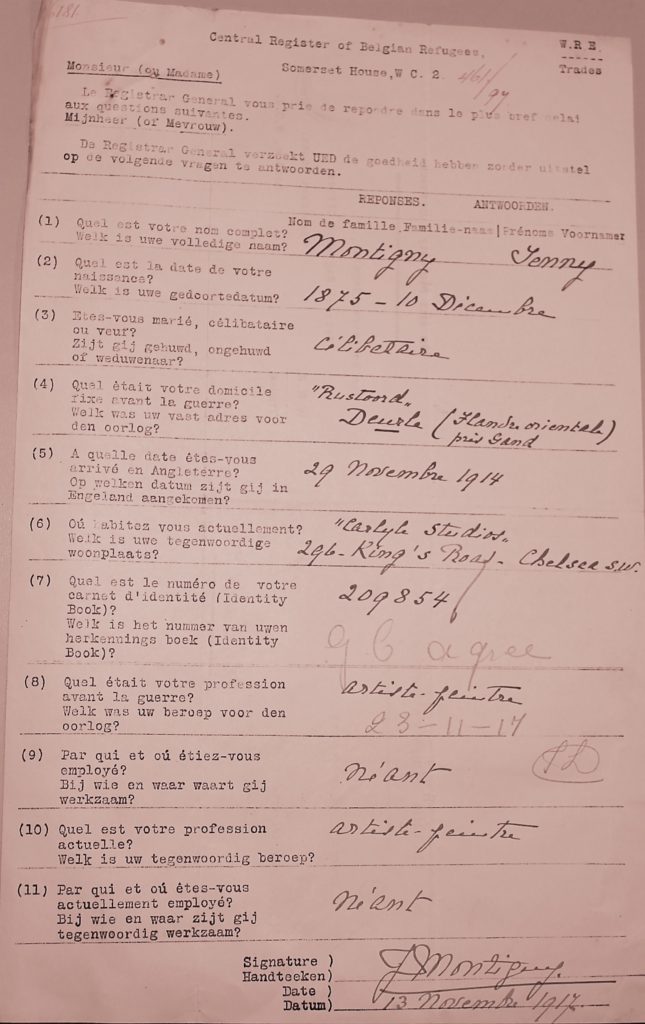

At the beginning of August 1914, the German army invaded our country. On 12th October 1914, German troops arrived in Ghent. Just in those turbulent first days of the war, on 6th November 1914, her father Louis Charles Auguste Montigny died at home, in Ghent. He was 79 years old. Jenny Montigny – like many of her fellow artists – went on the run. possibly shortly after her father’s death. She moved to London and registered as an artiste-peintre in the Central Register of Belgian Refugees on 29th November 1914. (photo credit : Johan Cauwels)

The years in London (November 1914 to April 1919) were crucial for her further artistic development. Jenny moved into Carlyle studios, on King’s Road in posh Chelsea. This exclusive and expensive London borough was very popular among artists and poets. The Carlyle Studios were inhabited by an international company of artists, including female artists like the Canadian Florence Carlyle (1864-1923). (photo credit : wikipedia)

It is often insinuated that Jenny Montigny deliberately followed Claus and his wife. In reality, Emile Claus and his wife Charlotte Dufaux arrived in London on 12th October 1914. They only stayed there for a few weeks before travelling to Wales. On 5th November 1914 Claus wrote to Cyriel Buysse in The Hague that he had left London. ‘I’ve run away from London: too many refugees of all kinds.’ In the same letter, Claus asked about the whereabouts of friends and acquaintances, including that of ‘J.M.’.

It is clear that in the first chaotic period of the war, Claus and his pupil had no contact and no idea about each other’s whereabouts.

Claus hardly got to paint in Wales. In early 1915 he returned to London, where he found shelter in the rectory of ‘Kings Weigh House Parsonage’ on Thomas Street, where a group of friendly artists such as Albert Baertsoen, Maurice Waegeman and Isidoor Opsomer lived. Even Cyriel Buysse came to visit. Although she was never mentioned, it seems quite plausible that Jenny Montigny by that time was also present in these circles. The fact that they most certainly met in 1915 is evident from this sketch made by Jenny in Hampstead Heath of her beloved mentor, in 1915. (photo credit : private archive)

In London, she was registered as ‘single’, even though she undertook the trip to London with her older brother Louis and his London wife Lilian Attneave.

Jenny and the Montigny-Attneave couple were never registered at the same residence during the war years. So Jenny enjoyed unprecedented freedom in London.

Artistically, she was flourishing. She exhibited in several London galleries, including the Dodeswell Gallery, the Camera Club and the New English Art Club. Her name appeared in many exhibitions for and by the Belgian artists in exile, well known all the way to Rotterdam. She joined the Women’s International Art Club, exhibiting with other artists such as Amy Katherine Browning (1881-1978) and Dorothea Sharp (1874-1955). (photo credit : Dorothea Sharp – National Museum Wales)

Strikingly beautiful are her engravings of Hyde Park and Kensington Garden. But also the sketches and drawings she made at the King Albert’s Hospitals with scenes of wounded Belgian soldiers and medical personnel. These sketches and etchings stand out in her oeuvre, because after the war she will never paint such, current, almost raw topics again. The question remains how and why the artist ended up in this unusual environment. Was she deliberately looking for traces of the war or drama that was taking place in the British capital? Or did she end up in this hospital for other reasons?

Emile Claus underwent surgery in London in August 1917. It is unsure whether he was hospitalized with health problems as a Belgian war refugee in a Belgian war hospital. And is that where Jenny was confronted with these war scenes? Does she get inspiration from other colleagues? The fact is that this series of engravings stand out fiercely from her other, rather carefree themes and work. (photo credits : private archive)

The 1920s

On 13th November 1918, Belgian troops walked the streets of Ghent and King Albert, Queen Elisabeth and heir Leopold made their solemn entrance into the city. Jenny Montigny only returned to Flanders in the spring of 1919. She remained in London, presumably because of Claus, who could not travel until he was recovered from his major surgery in March 1919. Afther his recovery Claus and Montigny will return to Belgium.

Little is known about what happened to Montigny when she returned to Flanders. Emile Claus did not immediately have the the desire to go back to work: “All summer I have sanded and cleaned, opened windows and doors to get the dirty ‘smell of the Hun’ out of Zonneschijn, and now finally a little rest, between my work, I am particularly concerned with my previous studies to put on the donkey every now and then and that gives me invigorating memories.” (photo credit Villa Zonneschijn : private archive)

Jenny had to sell her villa ‘Rustoord’ in 1920. She testified that her time in London had costed her a fortune. She moved into a more modest cottage on the banks of the Lys river in Deurne, next to the famous ‘Auberge du Pêcheur’. On a postcard with a view of these houses on the Leie to art-critic Frédéric De Smet she wrote ‘je niche ici’ (here I settle).

Montigny will remain there for the rest of her life, commuting between this house and her studio in the Dorpsstraat. (Photo credit : private archive)

It is in this period that Jenny Montigny develops into the painter of ‘les enfants de Flandre, riches de toute la santé de la terre flamande’ (translated: the children of Flanders, rich in all the health of the Flemish soil). In London, her interest in the human figure is already growing. Back in Deurle, Jenny focuses on the daily life in the village and the children playing in the fields, on the banks of the river Leie, in the village school of Saint-Joseph, where the nuns of Sint-Vincent de Paul with their typical ‘hoods’ grant permission to sketch the children in the classroom. (Photo credit: Gallery Oscar De Vos)

Her touch becomes heavier, as does her colouring. Her works continue to refer to Luminism, but shows more Fauvist influences. According to the testimony of housekeeper Zoë Ketels, Montigny and Claus regularly had heated arguments. The discussions between ‘mister’ Claus and ‘mademoiselle’ Montigny sometimes ran high, right through the closed doors of the studio. Moreover, ‘mademoiselle’ Montigny could be terribly unhappy and grumpy when her work did not go smoothly. How amiable she was in her daily dealings, she was so implacable about the quality of her work. And even ‘master’ Claus had to experience that.

After the war, the Paris Salons reopened, but it was at the Cercle Artistique de Gand and at the Brussels Salon that she achieved her greatest success, with exhibitions entirely devoted to her work. Her canvases are exhibited in Venice, Dresden, London, Berlin, Christiana (now Oslo), Buenos Aires, etc… They end up in the collections of MM. Hottat, Hottez, Van der Stegen, de Boe, Colombo (Milan), Loicq, in the Museum Charlier, in the Cuypers collection in Amsterdam, in the Musée Jeu de Paume in Paris (1929) and in the Musée de Douai (1930). (Photo credit: private archive)

After the unexpected death of Emile Claus in 1924, her life became more difficult, especially financially. It was Claus who often introduced her to and accompanied her in the artistic circles. Since 1922 Claus was no longer a member of the admission jury of the Ghent Salon. His influence was already less, the artistic taste changed and shifted to expressionism. Jenny Montigny did not follow and became artistically isolated. In a letter to art critic and friend Sander Pierron, written on New Year’s day 1927, more than 2,5 years after Claus’ death, she writes: “Je le ressens d’autant plus que, pour la première fois, j’affronte le public sous ma seule responsabilité, la mort de mon maître me laissant fort desemparée.” (translated : ‘I feel it all the more because, for the first time, I face the public on my own responsibility and the death of my master leaves me very distraught.’) (Photo credit: private archive)

Despite the moral and financial support from especially her sister Yvonne, her living conditions became dire. Canvases are painted on both sides, the rent is paid with a portrait of the landlord or his family. Her friends of the Cercle Artistique et Litteraire de Gand held a collection to discreetly purchase the work ‘Household Crafts’. She kept up her appearance, she strolled, in her characteristic white dress with hat, through the village or gardened in her flower-filled garden. Her house and studio remained, even after the death of Emile Claus, devoted to the master. Nothing was to be changed in the interior: his coat and hat remained hanging on the coat rack, as if he could pop in at any moment. (Photo credit: private archive, edited by Michiel Hendryckx)

Jenny Montigny died of cancer on 31 October 1937, in her house in the Pontstraat in Deurle at half past one in the morning.

She had her will drawn up over three years earlier. Jenny Montigny was aware of her lingering illness. On her deathbed she allegedly refused the priest’s assistance. She sent him walking with the words “I want to die as I have lived”. (Photo credit: J.Cauwels)

Epilogue

Our longing will never end… – Peter Verhelst

Today, anyone who visits the collection of the Fin-de-Siècle Museum (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium) will come across ‘The Portrait of Jenny Montigny’, painted by Emile Claus in 1902. She kept this radiant work in her home all these years, until her death in 1937.

In that early summer of the twentieth century, the master portrayed her in a sunlit garden as a young, somewhat shy young lady, dressed in a soft pink gown. With a pair of hesitant but open bright blue eyes, she stares at her viewer. At that time she had already been studying under Claus for about seven years, in fact insufficient to compete with the mostly academically trained male colleagues, but sufficient enough to claim a place in the art world of her time. On this page you already read how she fared. After her death, her name and oeuvre were lost in the margins of ‘great’ art history, although never forgotten in a small circle of collectors and fellow villagers.

Jenny Montigny was a remarkable personality: introvert but ambitious, highly bourgeois, yet bohemian, devout and headstrong at the same time. She was a child of her time: both in artistic choices and in life, things were different for her, as a woman, than for her male contemporaries. Her work was, and still is, overshadowed by a somewhat reluctant father figure, an overbearing master and an adored lover. Rarely was her work judged on its merits.

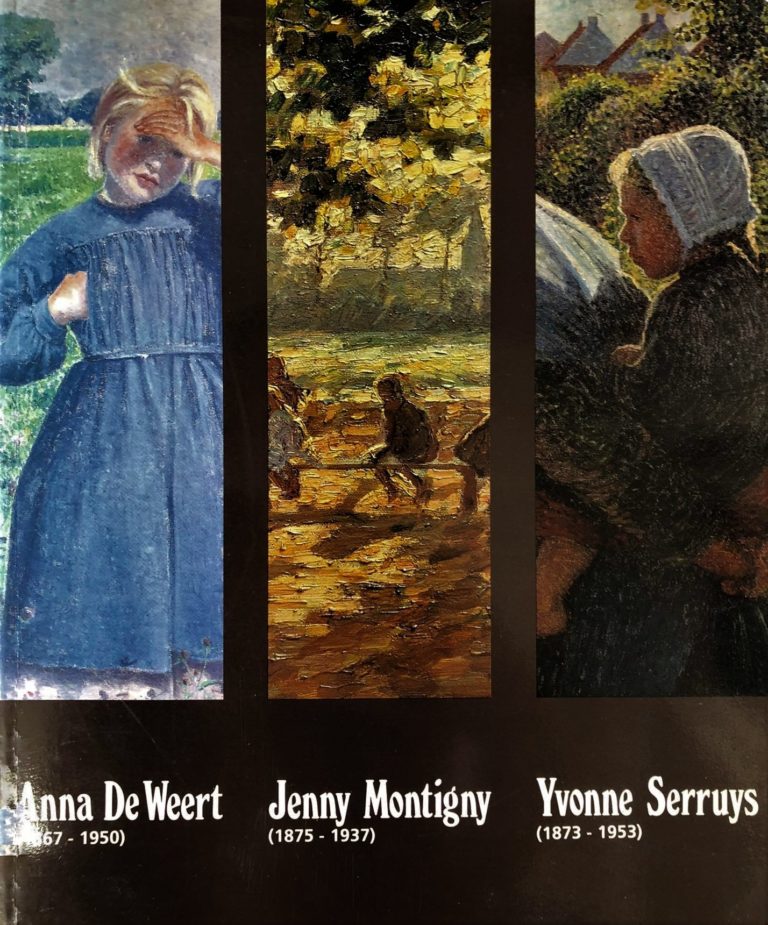

It was not until 1987 that a retrospective exhibition was devoted to the ‘Claus pupils’ Anna de Weert, Jenny Montigny and Yvonne Serruys.

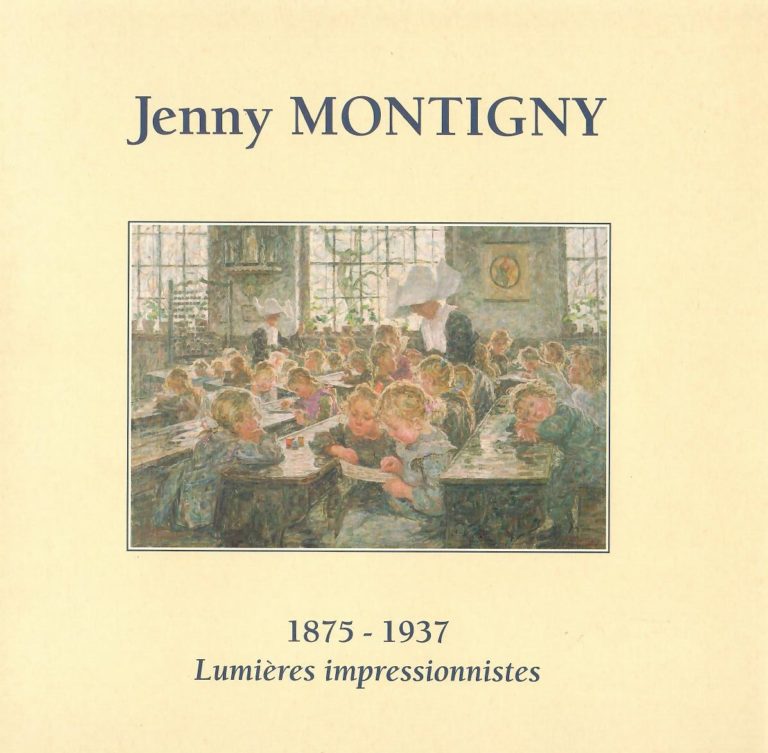

In 1997, based on the pioneering thesis of Marie-Hélène Wibo, she finally gets a solo exhibition in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Charleroi. (Photo credit : M. Ackx)

We, in turn, tried to tell her story anew, with new insights, in a different perspective, away from the shadows of the figures who seemed to dominate her, but whom she loved passionately and for whom she always longed.

What she wished for herself, we find a trace of in her will. ‘J’aimerais que soit faite un jour un exposition retrospective, très limitée, de celles de mes oeuvres dont je joint la liste, à faire à Bruxelles’ (translated : ‘I would like to see one day a very limited retrospective exhibition of my works with the list attached, to be held in Brussels’.) As we said before: she was modest, but still self-conscious enough to wish for a solo exhibition in the capital…

And what was to become of her splendid portrait by Claus? Jenny Montigny instructed her younger sister Yvonne, as executor of the will, as follows: Au Musée Claus, mais seulement après le décès de Mme. C., mon portrait fait par lui. Si elle avait prévu mon geste et l’avait refusé d’avance, je lègue mon portrait au Musée de Bruxelles, émmetant le voeu que les toiles de Claus sont soient groupées et mises en valeur.’ (translated: ‘To the Claus Museum, but only after the death of Mrs. C., I donate my portrait made by him. If she would foresee my gesture and would refuse it in advance, I leave my portrait to the Museum of Brussels, with the wish that the paintings of Claus will be grouped and valued there’.

After the sudden death of Emile Claus in June 1924, his widow Charlotte Dufaux transformed the studio in Villa Zonneschijn into a ‘museum’. Charlotte Dufaux only died in 1952, amply outliving the master and his ‘dearest’ pupil. And she did not want to accept the generous donation of Montigny’s portrait in 1937, as planned. So now we find Jenny Montigny’s image in Brussels, as a gift by Mrs Edouard Willems (or Yvonne Montigny) from 1941, surrounded by other works of Emile Claus.

The story of Jenny Montigny is not yet finished. It probably never will be. Because there are still so many pieces of the puzzle missing. Because not everything can be reconstructed. Because many sources are irrevocably lost. It was, is and will remain our intention to place her in the limelight as an autonomous artistic personality. Away from the conservative ‘male gaze’ of (mainly male) contemporaries, critics and art experts. Because she undeniably deserves it as an artist. And at the same time, her feminine vulnerability and touching affectionate attachment to that old master fascinate her, so that ultimately she was and will always be mentioned in the same breath with him. Something that, by the way, never bothered her, that she clearly did not care about, but that, on the contrary, she consciously cherished for the rest of her life…